Intellectual Property Newsletter – The aroma of innovation: how India just opened the door to smell trademarks

A New Dawn in Indian Trademark Law

Just last month, on 21 November 2025, the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (CGPDTM) quietly yet decisively broke new ground: it accepted what appears to be India’s first olfactory trademark application. The mark? A “floral fragrance/smell reminiscent of roses as applied to tyres” (Application No. 5860303), filed by Sumitomo Rubber Industries Ltd. What makes this milestone extraordinary is not merely the concept of a scent as a trademark, but how it was approved, thanks to a novel scientific vector model that translates a scent into a clear, reproducible visual chart. This ruling could change the face of branding in India. But it also raises serious practical and policy questions about enforcement and the balance between exclusivity and competition.

Why This Matters: Smells Were Always the Hardest Frontier

Trademark law worldwide has gradually expanded beyond traditional logos and names. Over the years, India has recognised sound marks (e.g., a jingle), colour combinations (e.g., a distinctive hue), and even three-dimensional shapes (e.g., product packaging). Smells, however, remained largely off-limits: they were seen as too fleeting, too subjective, impossible to represent visually, and therefore unable to satisfy the graphical representation requirement under Trade Marks Act, 1999 (Section 2(1)(zb)). The drafts and guidelines produced over the years, including the 2015 Draft Manual, admitted that while olfactory marks were conceptually possible, there was “no established mechanism” for representing them graphically.

In practice, attempts to register a smell trademark, often limited to a verbal description like “smell of roses”, were routinely rejected, following reasoning akin to the European test articulated in Sieckmann v. Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt, which required a sign to be clear, precise, objective, durable and reproducible. Under Section 9, marks that lacked distinctiveness or merely described a functional or generic product attribute were also barred. Smell marks, it seemed, belonged to legal theory, not practice.

The Sumitomo Petition: From Objection to Breakthrough

When Sumitomo filed its application on 23 March 2023 (as a “proposed-to-be-used” mark, due to e-filing constraints), the initial scrutiny was predictable. The Registry issued an examination report raising the usual objections:

- The scent lacked inherent distinctiveness; consumers might view it as merely an extra fragrance applied to tyres.

- There was no acceptable graphical representation, a mere textual description would not pass muster.

Faced with these obstacles, many applicants might quietly withdraw. Not Sumitomo.

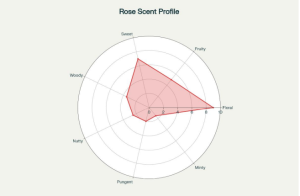

Instead, they engaged a research team from IIIT Allahabad, Professors Pritish Varadwaj, Neetesh Purohit and Dr. Suneet Yadav, who, in September 2024, submitted a seven-dimensional olfactory vector model. This model breaks down the scent into measurable intensities across seven perceptual dimensions: floral, fruity, woody, nutty, pungent, sweet, and minty. Each dimension is assigned a quantitative value, and the overall “signature” is displayed as a radar (spider-web) chart. Accompanied by a molecular-level description (“a complex mixture of volatile organic compounds that, when inhaled, evoke a rose-like smell”), and expert attestations, the submission made a compelling case that the scent could be objectively described, graphically represented and consistently reproduced.

To assist the registry in evaluating this unconventional evidence, senior IP counsel Pravin Anand acted as amicus curiae during hearings, bridging legal reasoning and scientific detail.

Here’s what that looks like:

Why the Registry Said Yes: Legal Reasoning Meets Science

In a carefully reasoned 25-page order, the CGPDTM, under Controller General Dr. Unnat P. Pandit, accepted the mark. Key findings:

- Graphical Representation

The olfactory vector and corresponding radar chart were judged sufficiently objective, precise, and reproducible to satisfy Section 2(1)(zb). The soluble, measurable description dispelled concerns of subjectivity and vagueness.

- Distinctiveness Through Arbitrariness

There is no natural or inherent connection between a rose scent and tyres. That arbitrariness, combined with decades of international use and brand recognition, provided a strong basis for distinctiveness.

- Non-Functionality

The scent adds no performance benefit such as traction, durability or safety. Its sole role is sensory and brand-identifying, which places it outside the exclusions of Section 9.

- Policy Considerations

The order acknowledges India’s evolving market and the importance of allowing businesses to adopt modern branding tools. Trademark law should not block innovation, it should facilitate it.

The mark is now advertised in Journal No. 2236 (24 November 2025), opening a four-month window for oppositions.

What This Opens Up: The Promise for Indian Brands

- A Realistic Route for Smell Marks

Companies in FMCG (e.g., spices, toiletries), hospitality (signature ambience), automobile interiors, perfumes, and even food products might now explore scent branding in earnest. A scent, once considered a quirky marketing add-on, may now function as a legitimate, enforceable brand identifier.

- Demand for Science–Law Collaboration

To satisfy graphical representation and reproducibility, future applicants may routinely require scientific analyses (e.g., GC-MS data, vector modelling). Over time, this could lead to a small industry of scent-mapping experts and labs.

- Growth in Non-Traditional Marks Generally

If olfactory marks become accepted, logically, other non-traditional sensations, perhaps taste profiles or tactile textures, may also be explored. India could evolve into a testbed for novel forms of branding, especially in sectors where sensory experience is central.

- Boost to India’s IP Modernity

This step aligns with broader economic and industrial ambitions. Indian companies would no longer have to rely solely on names, logos, or packaging, they can build brands with unique sensory identities. In a market heading toward $5 trillion, such differentiation can offer real competitive advantage.

But It’s Not All Roses: Practical and Policy Challenges Ahead

- Risk of Over-Broad Monopolies

A rose scent is hardly unique to tyres. Granting exclusivity to one company could hinder competitors across unrelated sectors, fabrics, stationery, cosmetics, or even food. The concern is that the trademark regime may start granting monopolies over common, culturally ubiquitous smells, thereby stifling competition and innovation.

- Enforcement Difficulties

Proving infringement of a scent mark in court will be arduous. Unlike a logo, a scent degrades over time, changes depending on ambient conditions (temperature, humidity), and may be hard to compare across products. Litigation may require expensive lab tests (ranging from ₹1 to 5 lakhs), electron-nose devices, or expert-driven GC-MS comparisons, a heavy burden, especially for smaller players.

- Scientific Uncertainty Over Odour Taxonomy

The seven-dimensional categorization used by IIIT is not universally accepted in scientific circles. There is no global consensus on “fundamental smell categories.” Later cases may see conflicting expert models, complicating the consistency and reliability of scent trademarks.

- Lack of Regulatory Framework

Until the Trade Marks Manual is formally updated with guidelines for olfactory, or other non-traditional, marks, acceptance could depend heavily on the discretion of examiners. That introduces uncertainty, unpredictability, and potential inconsistency.

- Market Realities vs Legal Protection

Even if a scent mark is registered, it is not clear whether consumers actually associate a smell with a brand in a consistent, recognisable way, especially for products like tyres. Without real-world consumer surveys or empirical evidence, claims of “distinctiveness” based purely on science may not hold up under scrutiny.

How India Compares Globally

- In the European Union, after the landmark Sieckmann decision, successful smell mark registrations have been extremely rare; most applications floundered under strict graphical representation standards.

- The United States has a handful of registered scent marks (e.g., for toys or candles), but only after heavy proof of acquired distinctiveness, usually involving years of sales, consumer recognition studies, and substantial marketing spend.

- In the United Kingdom, the same rose scent for tyres (used by Sumitomo) was registered in 1996, but with a much looser, purely verbal description. Compared to that, India’s new decision is far more rigorous and technologically grounded.

In short, India may now be among the most forward-looking jurisdictions when it comes to scent trademarks, provided its novel approach proves sustainable.

What Needs to Happen Next: Guidelines, Access, and Enforcement

- Regulatory Reform

The CGPDTM should update its Trade Marks Manual to include clear guidance for non-traditional marks: acceptable forms of graphical representation (e.g., vector charts, GC-MS spectra), evidence thresholds, and standards for reproducibility.

- Judicial Clarification

If the mark is opposed or litigated, India’s High Courts (or future IP benches) will have to clarify how far olfactory marks can go, especially regarding overlapping smells, “similarity,” and enforcement procedures.

- Support for MSMEs

To avoid a situation where only large firms can afford scent-mapping, policy measures, such as subsidised lab rates or shared-facility access, could democratise the opportunity for smaller players.

- Development of Detection Infrastructure

Investment in “electronic nose” technology, including low-cost, scalable tools, would make enforcement feasible and reduce reliance on expensive lab analyses.

Conclusion: A Significant Step: Cautious, But Forward-Looking

The CGPDTM’s acceptance of the rose-scented tyre mark represents more than a quirky novelty, it signals an institutional willingness to embrace scientific advances and align trademark law with evolving market realities. For now, the decision does not guarantee that all smells will eventually be protectable. But it does establish a credible pathway: if a scent can be described scientifically, visualised through a robust model, and shown to be distinctive, it may qualify.

This is not just about one brand or one scent. It’s about acknowledging that in markets saturated with logos and labels, sensory branding could become the next frontier, from the aroma of spices, to the scent inside a car, to the distinctive fragrance of a soap.

The road ahead will be contested, challenging, and technically complex, but also potentially transformative. For a country where smells already saturate daily life, from street-food stalls to festivals, this might just be the beginning of an aromatic revolution in IP.